A breakthrough in my maps-and-minis shootout minigame for White Line Nightmare, immersion, translation, and moving your body.

This One Goes There, That One Goes There, Right?

In my last playtest, I found that structuring shootouts with a focus on moving first felt off. The solution turned out to be a fairly simple switch in order of operations, and two playtests later I’m pretty convinced it’s the right design path to take.

The secret sauce is if you can see the enemy (or vice versa), nobody can move until you resolve that engagement. It might not always be an exchange of gunfire, but you figure out if someone’s suppressed, if someone gets hit, if you avoid harm, and then people can move. Narratively, you might advance while laying down gunfire or you might get suppressed and might only be able to move away from danger. You might choose to evade and duck low behind cover, moving to a wounded friend while the enemy fires at you. The point is, you can’t stand around in a dangerous position without resolving that danger first.

As always, there are some edge cases and some interactions that I undoubtedly haven’t come across yet but this revision has resulted in gunfights that feel closer to what I want. And what I want, as I’ve mentioned often on this blog, is the high-risk, grounded and tactical feeling of the final shootout from The Way of the Gun. The Gears of War games provide a similar touchstone.

Lost in Translation

If you’ve ever mag-dumped into a crowd of zombies in a video game, listened to music so loud you literally feel it in your chest, or even just joyously moved your body to exhaustion, you know there’s a visceral kinetic thrill that roleplaying games can’t grasp. The choreography in your ttrpg fight is imagined, and whether you create it from whole cloth or use examples from action movies your brain is not getting the same dopamine hits it would from external stimuli like thumping gunfire, sprays of pixels, and the DOOM music. I don’t think it’s necessarily a failing of ttrpgs either. The low-hanging fruit, the thing roleplaying game systems can do well1, is choice, not audio/visual overkill.

Another thing they do well is gambling. And gambling can be thrilling.

This Post Sat In Drafts For a While

At some point this post went off the rails real hard. Look, they can’t all be winners.

Violent2 things are exciting. Roleplaying games are bad at violence. Changing up what you’re actually trying to do with rpg rules sidesteps those problems. Provide choices, then make those choices risky. The excitement will follow.

Don’t try to choreograph fights in your rules. Leave that to the group’s individual imaginations. I do mean individual here – no matter how good a wordsmith you are on the fly, every player will see something different in their mind’s eye3.

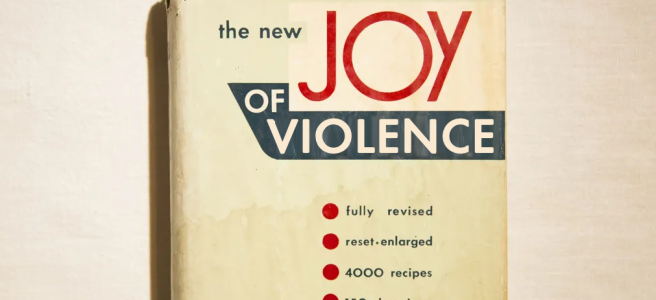

Finally, don’t let other people kink shame your imaginary bloodlust.

- RPGs sit at the center of a huge Venn diagram, not just choice and gambling. Interpersonal communication, imagination, math, art, attention to detail, the list goes on and on. ↩︎

- Fictional violence behind a veneer of stunt coordinators, VFX artists, or an author’s imagination. Real violence is bad, duh. ↩︎

- Assuming they even have one! Aphantasia exists! ↩︎